This Thursday marks the 40th anniversary of the eruption of the Nevado del Ruiz volcano. A tragedy that killed around 25,000 people, including her biological father, Carlos Alberto Gutierrez. jennifer de la rosstoat the time I only had one … A week of life. The disaster left hundreds of orphans, many of whom were adopted by Colombian and foreign families. Years later, many of these children are unable to be reunited with their biological families due to a lack of clear controls in their adoptions. Jennifer is one of them.

Adopted by a Spanish couple in 1987 Ten years ago, this Valladolid-based woman with slanted eyes, tanned skin and a Spanish accent set out on a journey to find answers to many questions about her origins. Chief among them was whether his mother, Dorian Tapaso, was still alive.

Thus was born the 2024 Seminci award-winning documentary “The Volcano Daughter” and the “excuse” and “boost” Jennifer needed to travel to Colombia. So he spent nearly a decade digging, metaphorically speaking, through the lava of the Nevado del Ruiz volcano. He knocked on dozens of doors and tried to connect the dots from the little information he managed to gather. “I decided to find out what happened on November 13, 1985.”

Jennifer learned of her first steps in life through her adoptive parents’ photo albums. “When I was one and a half years old, they picked me up at a family welfare facility (in Manizales). The last photo in the album had the Nevado del Ruiz volcano, and I realized that it was related to my story, what happened to me,” he explains.

For years, every time the anniversary of the disaster came, he remembered the past and became anxious. “I knew my father had died in this tragedy and my mother had left me in the care of a Red Cross lifeguard.” Just two pieces of information can build your biography. That’s why he embarked on this research trip. “I wanted to know more about what happened to me, the situation, my mother, if she’s alive, where she is… all the information I was missing.”

But what he found was that “information was missing, documents in the files were missing, and my mother’s name, Dorian Tapasco, was not listed in any records. I didn’t know if she was alive or dead. From there, the journey to find her and find out if she was alive began…” he recalls.

Visit to ground zero

The trip included visiting ground zero of the tragedy, which the filmmakers found “very shocking”. His memory includes a photo of his parents “on a lush coffee plantation.” And the Manizales orphanage where he spent his first months was “in a highland, green area.”

On the contrary, he admits that the town of Armero, buried under mud, lava and stones, is “so flat, so hot, that it has become a cemetery. There are ruins there, surrounded by vegetation, which are visited by many people every anniversary.” “Colombia was different than what I had imagined.”

But in the case of the Nevado del Ruiz volcanic catastrophe, the search for information can go in two directions. “There were also many people who wanted to know if I was their daughter. It was difficult to place myself in Armero and the tragedy. When I began to know the whole story, I realized that the real victims were the whole family who had lived searching ever since… Because, after all, I grew up in another country, so I don’t have any memory of the tragedy, of how it happened – he admits – but it was very difficult to find the pain and put myself in it, because there are so many people who have heartbreaking stories…”

Forty years have passed since the Armero tragedy, but not all the wounds have been healed. Those known as “lost children” remain unable to be reunited with their biological families.

Images of “lost children” who cannot be reunited with their biological families

But is Jennifer de la Rosa a lost girl? “The Armando Armero Foundation helped us find other people in the family. But to say with certainty that I am Armero’s lost girl, you still have to be able to contrast it with an adult human being. What you can say to me. It’s very difficult to recognize what happened. Those stolen words hurt. But one thing is for sure: we have lost all the memories that happened. He emphasizes that the fact that I can’t find my mother is because someone decided I shouldn’t, because the trial part of the file was signed and delivered in Spain. But if someone had verified that information and found out that Dorian itself did not exist, I would have been able to find it and everything would have been easier. “There was a lot of wrongdoing and it affected a lot of people like me.”

She says she has no relatives on her father’s side and “it’s very complicated without the father’s DNA,” but she feels a certain amount of joy on her mother’s side. “We were able to find something… (smiling to avoid any “spoilers” for his film debut).

After 10 years of searching for answers and making documentaries during that time, the filmmaker asserts that Volcano’s Daughter has given her “a story. I can now understand where I was born, what happened to me, why I was adopted. It gave me peace.”

After watching the tape, you can’t help but wonder how Jennifer’s biological family went through this search process and ask Jennifer. “The first time I went to Colombia, I hid it from them, but I couldn’t help but tell them about my second trip,” she confesses. “They told me that what I was looking for was normal things and that they wanted to know my country and where I was from.” Their honesty came as a “shock” to her, she admits. “After watching the documentary, they said they were hurt that I had suffered so much and that I had not yet found answers. And in my case everything was legal,” he clarified.

But the exploration isn’t over yet. “Now, I have to go back there and watch ‘The Volcano’s Daughter,’ and I hope it helps me find Dorian and finish the story. That was the intention I had when I started, to uncover the truth. When I first went to Colombia, I thought it would be a shorter path, but it was really long.

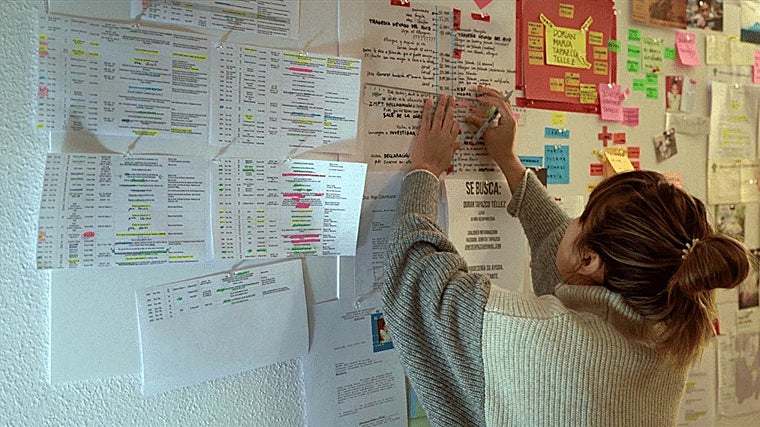

At one point in the documentary, Jennifer shows a mural containing all the information she has collected.

But amidst so much pain, there was also hope. “The great thing about all this is that I hope that many people who came from Almelo and now live here in Spain will watch this film and see a reflection of themselves. The pain is still there, but they want to continue to condemn what happened. And I hope that this documentary will help in some way to focus on all the grievances that happened in 1985 and all the separations that remain to this day,” he asserts.

This Thursday, the 40th anniversary of the tragedy, Jennifer de la Rosa will be visiting Armero, where her documentary will be premiered. “It will be projected there, and finally the circle I opened will be closed.”