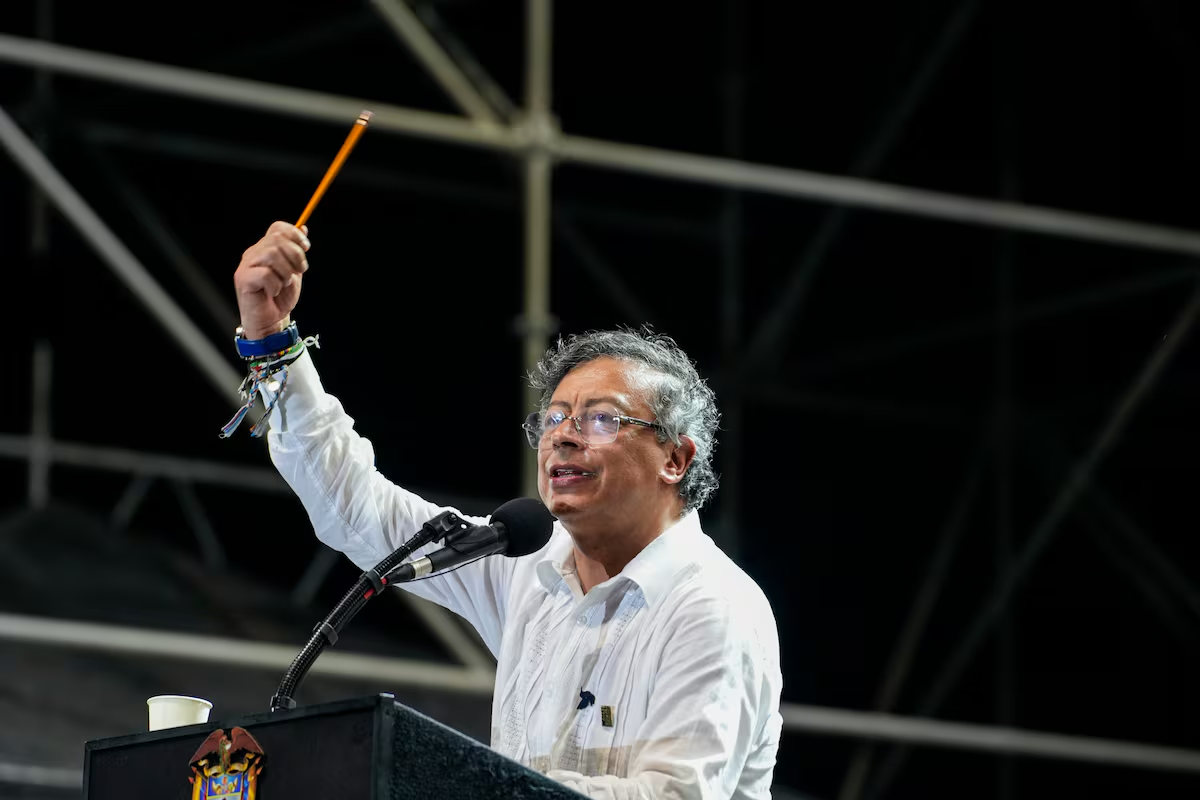

President Gustavo Petro ordered “all intelligence levels” of Colombia’s public forces to stop “transmitting communications and other transactions” with U.S. security agencies. This measure, announced in

The president’s order came in response to a report on the CNN television network that Britain was halting intelligence sharing with the United States on suspected drug-trafficking vessels in the Caribbean because it “does not want to be complicit in U.S. military attacks and believes these are illegal,” people familiar with the matter told U.S. media.

Britain’s control of Caribbean territories such as the British Virgin Islands, Anguilla and Bermuda has made it a key ally of Washington in spotting suspicious ships. According to CNN, that collaboration has ended.

Mr Petro has been highly critical of US President Donald Trump over the bombing, which was first concentrated in the Caribbean and then spread to the Pacific Ocean. “Once again, I call on the US government to return to respecting human rights in the fight against drugs. Their act of firing missiles at poor boatmen in the Caribbean, whether part of a drug lord’s cocaine transport operations or not, is nothing short of an extrajudicial execution of defenseless Caribbean and Latin American citizens,” the Colombian said in the publication of X newspaper a few days ago.

“The same missiles that fell on Gaza will fall on the poor people here in the Caribbean,” Petro declared at a summit between the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (Serac) and the European Union (EU) in the coastal city of Santa Marta over the weekend. And while the final statement did not explicitly condemn President Trump’s military operations, there was a shadow overshadowing the event. Brazilian Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva stressed that “the threat of the use of force is once again part of everyday life in Latin America and the Caribbean,” while Estonian Kaja Kalas, the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs, said in an interview with EL PAÍS that the EU is “concerned about the global phenomenon of organized crime” and that this is an issue that “must be tackled together.”

Mr. Petro did not specify specifically which agencies would stop sharing information with Washington, but when he spoke of the “intelligence level of public forces,” it is presumed that he was referring to the Directorate of Police Intelligence (Dipole), the Office of Naval Intelligence, the Special Air Intelligence Service, Cyberspace, the Directorate of Military Intelligence, and the Directorate of Counterintelligence. Cooperation with the United States on this issue is critical for Colombia, especially as organized crime plagues the country, with multiple armed groups spread across the country and funded by the illicit economy, including drug trafficking, illegal mining, human trafficking, and extortion.

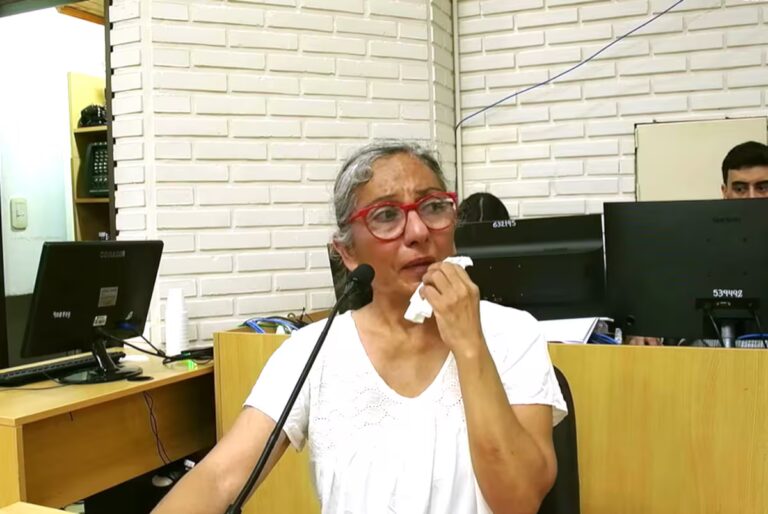

The U.S. attack has put Colombia, the world’s largest producer of cocaine, increasingly on the radar. Of the 18 ships that have sunk so far, at least four have some connection to the country. Petro has defended the September 15 attack in the Caribbean that left a Colombian man, whom he identified as fisherman Alejandro Carranza, dead. The attack “probably” occurred in the country’s waters. The next day, American forces sunk a submarine believed to be carrying Colombian Jonathan Obando Pérez, but he survived the bombing. The man was rescued by the U.S. military and returned to Colombia. Washington sent Obando Perez to be charged under Colombian law, but Obando Perez was released because he could not prove he had committed a crime.

On October 17, another ship was attacked in the Caribbean. US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth then linked it to Colombia’s last armed guerrillas, the National Liberation Army (ELN). And on October 22, Hegseth acknowledged that one of Washington’s first attacks in the Pacific occurred “off the coast of Colombia.” It is unclear whether the ship left Colombia or whether there were Colombians on board.

So far, there has been no response from the United States to Colombia’s announcement.