In the history of international relations, doctrine constitutes guidelines that guide the foreign policy of a country or a group of countries. A classic example in Latin America is the Calbo Doctrine (1868), which states that resident aliens who suffer any harm in their host country should seek recourse in the courts of that country to avoid jury intervention or the use of external force. The Drago Doctrine (1902), which rejects the use of violence (war, military occupation, or bombing) by creditor states to coerce debtor states in the event of bankruptcy, or the Estrada Doctrine (1930), which rejects the practice of recognizing governments for political reasons, given that it does not create qualifications for the legitimacy of de facto governments among previously recognized states.

The United States has had several doctrines that have guided its foreign policy, including the early Cold War Truman Doctrine, which positioned the United States as the “defender of the free world,” but few have been as influential as the Monroe Doctrine, created in 1823 with the powerful words “America for the American people.”

During the Trump I administration, it was said that there was no consistent foreign policy doctrine that would facilitate responding to challenges to the international system, despite the president’s emphasis on unpredictability as a factor for success, to the point of being called an anti-doctrine (Tovar Ruíz, 2017).

The Trump administration, entering its first year in office, has applied a set of policies that visualize an earlier doctrine colloquially named “Don Roe,” combining the names of the president and his predecessor, James Monroe, although this is perhaps a new interpretation, such as that of Secretary of State James Olney, who expanded the Monroe Doctrine in 1895 to make the United States the arbiter of all border disputes in the Western Hemisphere.

“Today, the United States is de facto sovereign on this continent, and its decisions are the law of what it limits its intervention in,” he said at the time. Then, in 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt went even further, asserting the United States’ right to intervene in the internal affairs of the hemisphere to prevent European powers from intervening militarily to demand payment of promises, assigning the United States the role of “international police.”

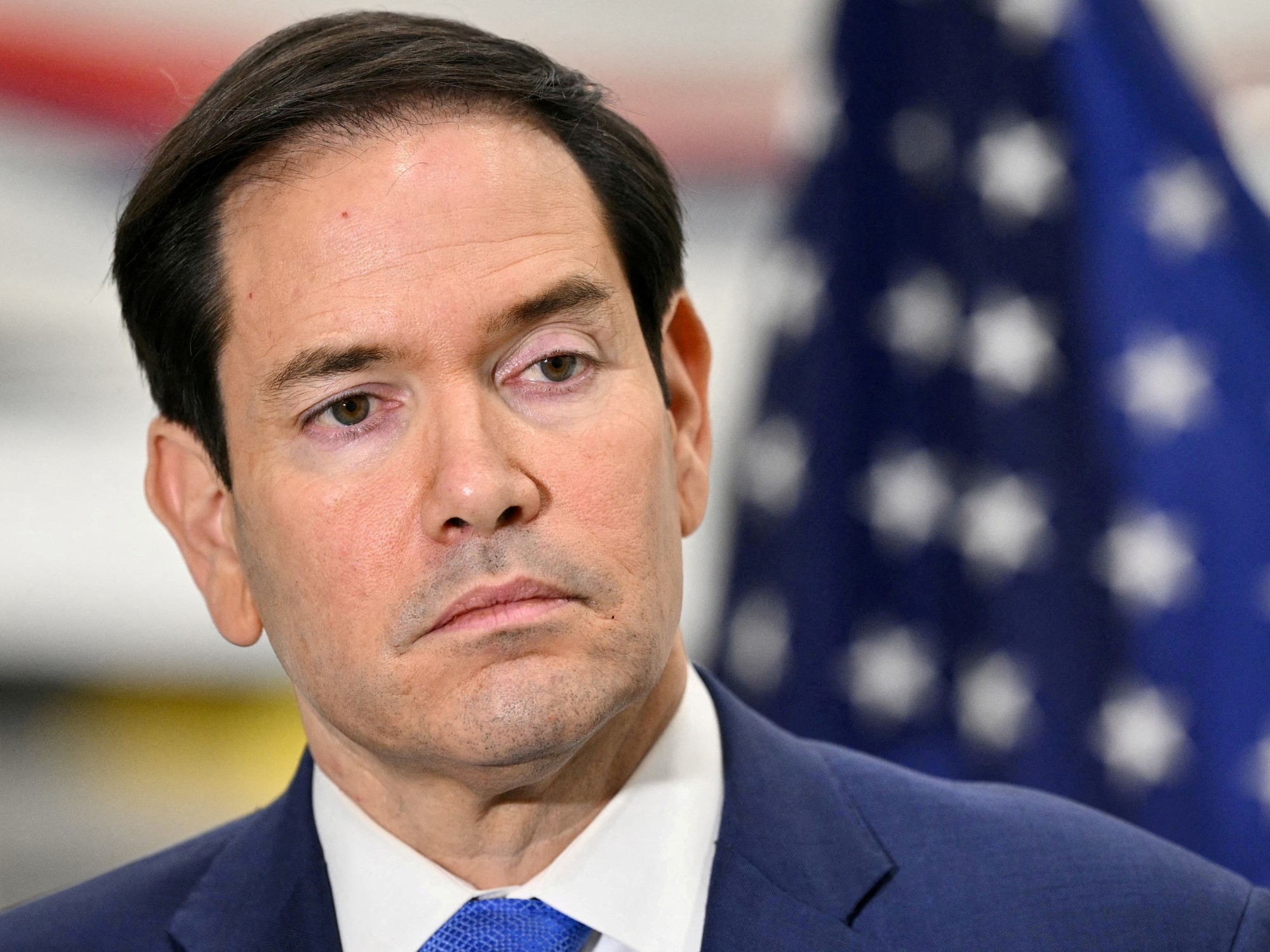

This new interpretation, or corollary, was revealed at the G7 Foreign Ministers’ Meeting in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Canada. In Washington, Secretary of State Marco Rubio argued that his military had the right to operate in “that hemisphere” and that Europe would not decide the legality of operations against Caribbean boats allegedly laden with drugs.

Later, Pentagon Secretary Pete Hegseth announced how the U.S. military’s offensive operations against suspected drug traffickers in the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific Ocean were formalized, overcoming the earlier definition of a “non-international armed conflict” in which they were initially justified.

‘Narcoterrorism’ has been identified as Washington’s hemispheric priority, taking up a concept from the end of the last century, rooted in the experience of fighting Colombian drug cartels in conjunction with anti-government guerrillas, and understanding the use of drug trafficking as a strategy to advance the objectives of anti-American governments such as Cuba, Bulgaria and Nicaragua (Ehrenfeld, 1990).

Since this “Donroe” doctrine signals support for pro-Washington leaders in the region, rewards them through trade agreements that reduce the impact of general tariff increases (on Argentina, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Ecuador), and promises punishment for all drug and anti-American acts in the Americas, it is not strange to think that Cuba will remain on the list of “Rubio’s corollaries” after military pressure against Venezuela.

Trumpist unpredictability is relativized and opens the door for states to decide between acquiescence, accommodation, or confrontation, which is not easy for any type of autonomy.