This incident has been told since 1550 by Giorgio Vasari, a Renaissance art historian and author of The Lives of the Artists.

Pope Benedict IX sent his courtiers to Florence to search for drawings in order to select an artist to decorate Rome’s ancient St. Peter’s Basilica. He encouraged Giotto to be remembered and admired Giotto’s paintings in Campo Santo in Pisa.

A messenger came to him and asked for a sample of his art. Giotto drew a circle on the paper with the brush he had in hand and said, “This is the picture.” The messenger asked for further work, to which he replied that it was enough, but that he needed to explain to the Pope that he had drawn up this plan without a compass.

Pope Benedict IX, who received this paper, was amazed at the accuracy of the freehand outline, declared its author an ace, and summoned him to Rome. History has given rise to the saying “rounder than Giotto’s O” (più tondo dell’O di Giotto) to describe perfection.

Three hundred years later, another historian, the Englishman John Ruskin, wrote that there was reason to doubt Vasari. The Pisa paintings are by Francesco da Volterra, not Giotto. The Pope at the time was Boniface VIII, not Benedict IX.

Nevertheless, Ruskin considered this incident to be true, since the excellence of this circle testified to Giotto’s skill and stubbornness, his talent and clumsiness. The words that inspired it, he said, encapsulate this mixture of neatness and directness. Tondo means round, but in Tuscan language it means rough.

Giotto was a man of the people. He is the son of a farmer, and when he was a child he used to raise sheep and draw pictures of sheep on flat stones. They were so well made that the famous painter Cimabue adopted them when he was only 10 years old. The values soon reversed, and Dante wrote in Purgatory that the student had surpassed the instructor.

He was more of a wall decorator than an artist. There was an environment that didn’t exist at the time: a workshop rather than a studio. There he painted tempera paintings and prepared frescoes for the church. Ruskin said he worked to please the diocese “unencumbered by philosophical abstractions and critics.”

The climax of his work was the Arena Chapel in Padua, completed in 1305. Enrico Scrovegni, a banker like his father Reginald the Miser, provided the financing for the construction. In return, Giotto painted Enrico above the front door and handed Maria a model of the chapel.

The surprise that this small church, recently revisited, evokes occurs as soon as you enter and look up at the ceiling. The ceiling is painted a deep indigo to mimic a starry sky, in contrast to the sunny day outside.

The amazement is even greater when you gaze at the walls, which seem to vibrate with the clarity of the colors, the hustle and bustle of the people, and the brilliant glow of dozens of golden halos. There is not a square centimeter that is not occupied by a painting, such as a magnificent comic book rectangle.

There are frescoes depicting great feats. Mary’s pregnancy. Childhood of the Nazarenes. His death and resurrection. His apocalyptic return to judge the living and the dead. The vices and virtues of troubled humanity.

These two innovations, elegant colorism and painterly narrative, merge into Giotto’s important invention: realism. This is evident in the opening story of pain and love between María’s parents, Joaquín and Ana.

An old Joachim, expelled from the synagogue for being childless, hides in the countryside, humiliated. An angel appeared to Anna and told her to go back to having sex with her husband. Because Jehovah will ensure that she will be able to give birth even in her old age.

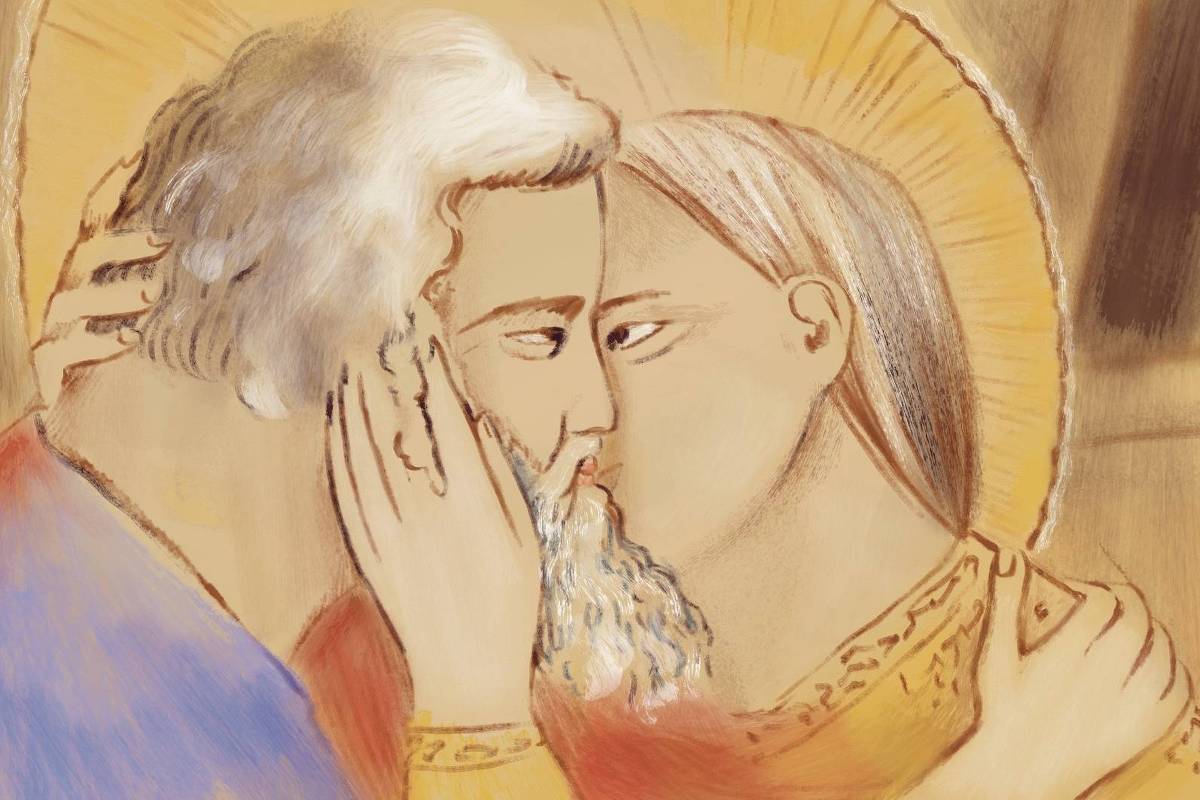

The two meet again in Jerusalem, and Giotto shares the first kiss in the history of art. Joaquim hugged Ana and she stroked his gray beard. Their lips touch, filled with tenderness, and Anna’s friends smile with joy. Later, during the Passion scene, another kiss takes place, but this is an insincere kiss. This is the kiss that Judas gives to Jesus in order to betray him to the Roman police.

Giotto’s realism replaced the dry formalism of Byzantine iconography with static statues and majestic gods. He rebelled against centuries of tradition, recorded people’s sorrows and joys, and stood at the forefront of art.

Sometimes tough people and art. Giotto did not know the flat perspective that only appears in Brunelleschi, so his figures are incongruous, squat, and ridiculous; children, for example, are miniatures of adults. Even Ruskin, who considered him a unique man and a wise man, admitted that he was “not one of the most talented painters.”

In a word, it was rough. Whatever it is, Ana and Joaquin’s kiss is more rounded than Giotto’s.