credit, Getty Images/BBC

-

- author, Chris Baraniuk

- roll, BBC World Service

The Pope is watching. This is a much better piece.

This kind of idea may have occurred to Guglielmo Marconi (1874-1937), who in 1932, under the supervision of Pope Pius XII (1857-1939), installed a special antenna in the gardens of the Vatican.

The antenna was part of a new radio link between the Vatican and the pope’s summer residence in Castel Gandolfo, Italy.

But it was more than just a radio link. It was a microwave link, a very high frequency radio wave.

Mr. Marconi also installed a portable microwave communication system attached to the Pope’s car to connect him to the Vatican during his travels. Some claim this was the first mobile phone, but it certainly wasn’t portable at all.

Thirteen years earlier, Marconi had shared the Nobel Prize in Physics with Carl Ferdinand Braun (1850-1918) for his contributions to wireless telegraphy.

The era of radio was in full swing. However, Marconi began using microwaves to tap into a part of the radio spectrum that had very specific properties.

Microwaves can transmit vast amounts of information. You can also cook food and interfere with enemy electronic equipment. Microwaves can also help uncover the very origins of the universe.

credit, DeAgostini/Getty Images/BBC

Pipipipi

Long before Marconi created a microwave phone for the Pope, someone else was experimenting with similar frequencies.

In the late 19th century, a brilliant Indian scientist named Jagadish Chandra Bose (1858-1937), who is unfortunately now largely forgotten, developed some of the world’s first microwave technology.

Mr. Marconi certainly owes some of his leadership role to Bose.

Sitting in a clifftop cabin in Newfoundland, Canada, he spent hours listening to a deluge of noise through his headphones, until the predictable thing happened. Beep beep beepthe letter “S” in Morse code.

He frantically handed the receiver to his colleague and asked, “Can you hear anything?” he asked.

It was an incredible feat. Those radio waves traveled more than 3,000 miles from southern England across the open sea. At the time, the record for long-distance radio communication was only 129 km.

credit, SSPL/Getty Images/BBC

Some have since questioned whether the infection actually occurred as Marconi said. But recent research shows that the feat was theoretically possible even with primitive equipment.

This device was called a coherer, a simple radio signal detector. Although records are somewhat hazy, it appears that Marconi’s coherer was designed by none other than Bose.

“He created a fascinating instrument,” says Bose’s biographer Sudipto Das. But Bose was probably too ahead of its time.

On the other hand, microwaves in the early 20th century had few useful applications because lower frequency radio waves were not yet available.

Bose left physics to concentrate on the field that most interested him: plant physiology. As a result, he “almost faded into oblivion,” Das says.

magnetron popcorn

However, World War II (1939-1945) renewed the importance of microwaves.

Radar allowed the military to detect enemy aircraft by reflecting radio signals. And a microwave device called the magnetron, developed in Britain in 1940, turned out to be one of the most powerful and effective radar technologies in the world.

Its incredible range and accuracy, combined with its compact size for mounting on aircraft, gave the Allies significant advantages that helped them win the war.

The microwave-emitting magnetron also inspired Raytheon engineer Percy Spencer (1894-1970) to invent the microwave oven in 1945.

As he walked next to the magnetron in his lab, a peanut bar in his pocket began to melt. Then popcorn packages started popping “all over the lab,” the Reader’s Digest report recalled.

credit, SSPL/Getty Images/BBC

This happened because the microwaves excited the molecules in the food at a specific frequency, causing them to vibrate at the same frequency. The resulting friction heats the object.

For microwave ovens, the frequency chosen is 2.4 gigahertz (GHz), which is the same frequency used by many Wi-Fi routers.

But of course, a router emits a signal at a much lower power level than a microwave oven. So you can’t make popcorn just by surfing the web.

According to Caroline Ross of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), choosing the right frequency for cooking is very important.

2.4 GHz microwaves penetrate food well, and this frequency also allows for uniform absorption of the radiation by food molecules.

“For example, as you increase to tens of gigahertz, the penetration depth becomes very small,” she explains. “So pretty much everything blocks it, including water in the air.”

Microwaves are special because of their ability to interact with matter at specific frequencies.

Admittedly, heating up leftover dinner may not be all that fun. But what about using microwaves to induce noise into people’s heads?

Havana syndrome

Military personnel working near a large microwave radar facility built during World War II later recalled feeling the radar activated.

“If you stood near the antenna you could hear the repeating sound of the radar,” one witness wrote in the 1950s.

James Lin, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago, heard about these stories and set out to recreate the effect in his lab in the 1970s.

“I basically used myself as a guinea pig,” he recalled, explaining how he set up a microwave antenna and pointed it directly at his head.

Lin suggested that the microwaves may have caused pressure waves in the head, which were perceived as sound. And to avoid draining his brain, he kept his energy levels low.

“I could hear the pulse,” he says. “Since you’re alive… maybe it wasn’t that bad.”

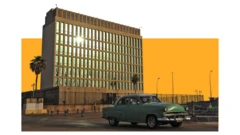

This phenomenon became known as the microwave hearing effect and helps explain several mysterious illnesses reported by diplomats around the world. The most famous incident occurred in Havana, the capital of Cuba.

credit, AFP via Getty Images/BBC

Victims of so-called Havana syndrome report hearing strange, dissonant sounds, increased pressure in the ears, dizziness, nausea, and memory loss.

Could the enemy be directing microwave beams at those people?

While microwave weapons do exist, the weapons discussed in public tend to affect machines rather than humans.

The US military, for example, has missiles that can destroy enemy electronic circuits using microwaves. Microwaves can even destroy drones.

Meanwhile, Lin has developed ways to use microwaves in medicine, including treating muscle diseases and abnormal heartbeats.

In this case, he claims it is possible to insert a small microwave-emitting device into the heart through a catheter and destroy the abnormal heart tissue. This technique, now widely used, is less invasive than open-heart surgery.

“You can just send a high-power pulse, or microwave, and it burns out the tissue,” he explains.

the universe is talking

Microwaves not only save lives, but also help us understand the origin of the universe.

In the 1960s, radio astronomers Arno Penzias (1933-2024) and Robert Woodrow Wilson experimented with using a large horn antenna as a radio telescope in New Jersey, USA. But they only tuned in to annoying hisses and noises.

Initially, they thought pigeon droppings on the antenna were the culprit. So they chased away the birds and cleaned up the mess.

But it wasn’t the pigeon’s fault. Penzias and Wilson were hearing the sounds of the universe itself.

“This is an ancient portrait,” said Sean McGee from the University of Birmingham in the UK.

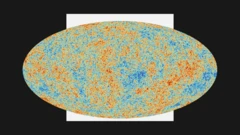

Penzias and Wilson discovered that what we today call the cosmic microwave background radiation is a trace left by the Big Bang, the explosion that created the universe about 13.8 billion years ago.

For this work, Penzias and Wilson won half of the 1978 Nobel Prize in Physics, jointly with Pyotr Leonidovich Kapitsa (1894-1984), for fundamental inventions and discoveries in the field of low-temperature physics.

credit, ESA/Planck Collection/BBC

The residual radiation detected by Penzias and Wilson exists throughout the universe and is responsible for a small portion of the static electricity on analog television screens.

In other words, until the advent of LED TVs, people watched remnants of the Big Bang in their living rooms.

The satellite has helped astronomers map the cosmic microwave background radiation. The fluctuations are recorded as small temperature differences.

“We are all the result of quantum fluctuations in the early universe that seeded galaxies,” McGee explains.

Today, all satellite-connected international calls use microwave ovens. This is undoubtedly a huge improvement over the device Marconi installed in cars for Pope Pius XI in the 1930s.

It is very appropriate for people to use microwaves to communicate in their daily lives. After all, this is the way the universe speaks to us, and it helps confirm our understanding of the greatest story of all time: how it all began.

This report was produced in collaboration with the Nobel Prize Supporters and the BBC.