“Downriver, we saw tourists on bicycles. Here, we don’t even have that. This pink building is located in an area that is not very close to the center or to parts of the M-30 that have been filled in and rewilded. It is even more artificial, but it has a similar impact on rental prices,” says researcher Javier Gil. This was one of the most unusual stops on a walk that members of the Group for Urban Research (GECU) and the Madrid Tenants Union took part in last Thursday, November 6, via Puerta del Ángel as part of an international conference. Mapping platformed works in the digital city.

pink house style barbie Complemented with terrace light bulbs indie In a sterile hall that reflects the lack of soul in the space. This is a perfect example of the particular real estate process that this part of the Latina neighborhood is going through. Gentrification is artificial and almost non-existent. A business that causes this doesn’t just start up and end. As a result, yes.

“They started at 150 euros a night, now it’s 80 euros, but it’s still mostly empty and everyone who comes is working rather than seeing the city,” Alberto Crespo, a member of the tenants’ union who is preparing a doctoral thesis on the housing situation in this area west of the capital, says of the accommodation. Besides these hostels, a quick look at real estate portals shows ground floors of less than 40 square meters for 1000 euros. A few years ago, no landlord would be paying more than 400 euros a month at this price. To rent a larger house on Karamuel Street, less than 90 square meters, you will have to spend almost 2,000 euros a month. The previous price would have been around 800-900 euros in the worst case scenario.

Javier Gil commented that one of the businesses acquired by the former lottery management company Madeline Vulture Fund, a large holder that used Puerta del Ángel as a testing ground, has been closed for two years. “They prefer that to the opening of another similar business that does not contribute to the transformation of the neighborhood. They look for something like a cafeteria or restaurant that works for them in the Tirso de Molina market, which is managed by a fund that also owns Sala Equis in central Madrid. That is the model that they are trying to export to the whole neighborhood,” he explains.

This part of Puerta del Ángel is a story of tenancy, punctuated by smoke and emptiness. In the case of Legazpi, in other parts of the neighborhood and in other settings, there can be a direct correlation between improvements in infrastructure, communications, and provision of green space where the burying of M-30 means higher housing prices. But on Caramuel Street and many of its surrounding streets, Madeline has been responsible for buying vertically owned buildings (with one landlord on all floors) and converting them, with the ground floor turned into “fashionable” businesses and the houses turned into seasonal rentals, raising average rents.

No. 14 is a case in point, with a closed wine cellar followed by several floors, and renovated windows showing which floors were replaced. Once the contract was executed, Madeline did not impose an unaffordable increase or offer the possibility of renewal. “What is not renewed are the tenants who are holding on, in this case because of old rents. Those who are holding on are distinguished by the windows,” Alberto argues.

In other cases, those who stay do so with greater difficulties. On Juan Tornello Avenue, a few meters away from the store that served as Madeline’s operations center until neighborhood pressure forced her to relocate, there are only two unrenovated windows, both on the upper floors. “One of my neighbors implemented that strategy. we will staywith support from the Tenants Association. Prove that you are continuing to pay the amount you were paying before the increase, threat of eviction, or lack of alternative housing. This usually involves a judicial process that lasts about three years and involves the owner depositing the money in court because they don’t receive it. “While tenants continue to comply with their obligations, the loss of income for owners reduces the power gap between the two parties,” says Alberto Crespo.

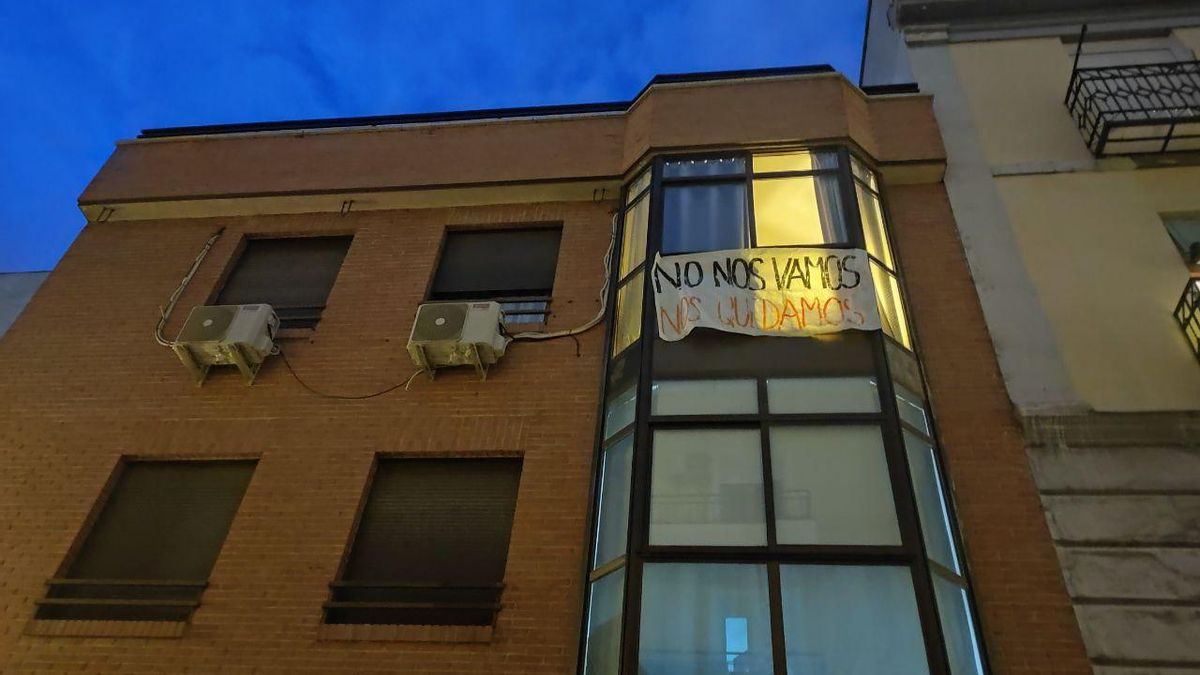

Struggles are currently taking place in two blocks in Puerta del Ángel, where all or most of the residents are organizing against the impending or already ongoing expulsion process. One of them is on Calle Antonio Zamora, with a banner in its window with the message: “We will not leave, we will stay.” The problem is with windows. The building is facing an eviction attempt by investment fund Dramere SL Mercedes. Josés Moreno, one of Spain’s richest women and the largest shareholder of Grupo Planeta, is part of this group and intends to evict 10 families without even offering the possibility of paying additional fees. “He wants to create accommodation for tourists,” says Javier Gil.

In front of another of Madeline’s colorful buildings, scholars explain the processes that led to the current dramatic housing situation. The legal reforms promoted by the governments of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero and Mariano Rajoy were hardly amended during the presidency of Pedro Sánchez (even more so in this last Congress: “Jants have blocked the tightening of regulations on the abuse of seasonal rents applied to permanent tenants”). Change in Madrid was reinforced by the local government, including the sale of 1,800 social housing units to the Blackstone Vulture Fund during Mayor Ana Botella’s tenure.

In the face of the mortgage and banking crises, corrections promote “speculative dynamics” that are not necessarily caused by a lack of supply or high demand. “We are seeing the practice extend to areas of depopulation. Housing is a system of expectations, disconnected from the real value of things,” emphasizes Javier Gil.

It’s a matter of expectations. A story of a fashionable ecosystem that is, or seems to be, suitable for “digital nomads.” These include professionals in fields such as technology and finance, temporary workers or students on expensive graduate courses who can pay up to 1,500 euros a month for a room with a bathroom and kitchenette. Funds operating in Puerta del Angel are taking advantage of this. For this reason, the wealthiest unsettled people coexist with the popular classes and workers from more precarious sectors. Just as this district, driven primarily by immigrants from Extremadura and Andalusia, abandoned its status as a suburb without fully embracing its status as a center, its inhabitants now live in a kind of strange balance between the consequences of speculation and resistance to their own specificity.

The Tirso de Molina market, located in the middle of the pedestrian zone, is home to a thriving high-end cafeteria and restaurant. However, a few meters away, a pizzeria with a similar profile continued to operate for several months. Long-established bars and dry cleaners with sugar cane signs testify to a time that refuses to become history. The tug of war continues. It can also be seen in the eroded frames of facades and apartment windows that have been abandoned by estates that refuse to renovate unless the tenants give up first. People who just want to open their doors and windows to ventilate their home or greet their neighbors.