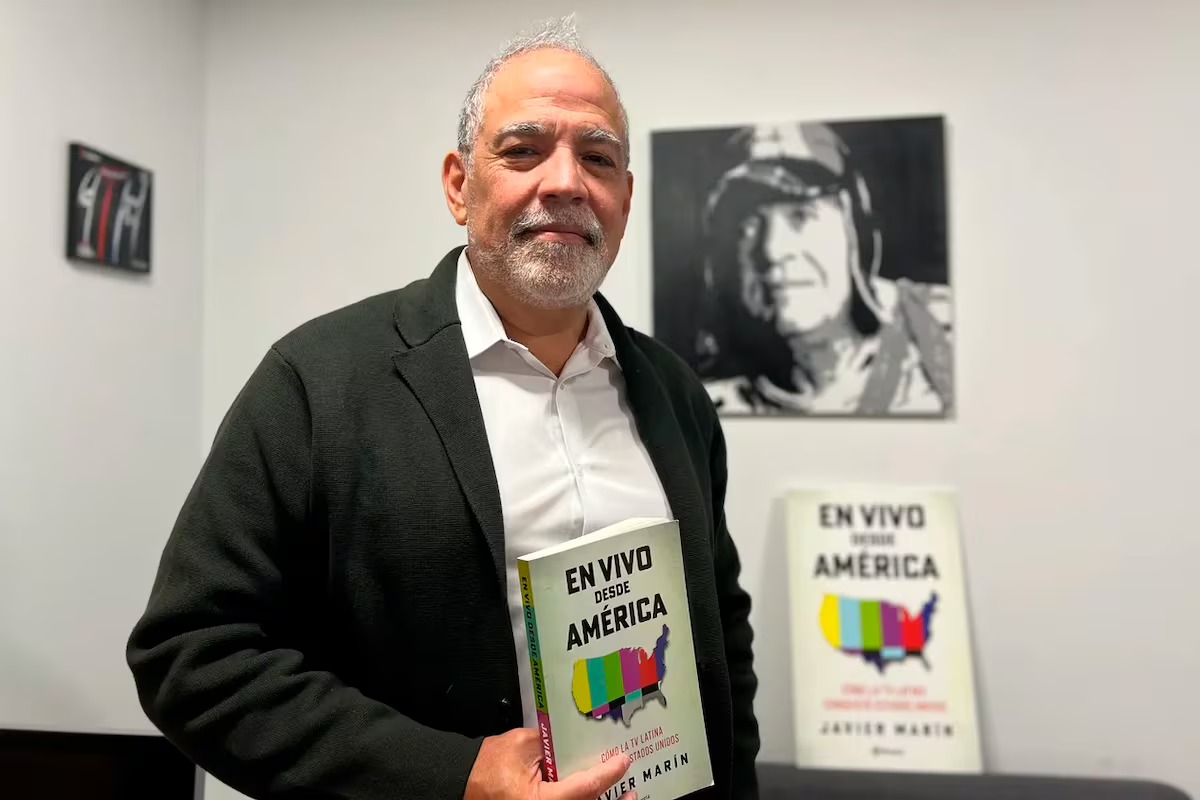

You learn from other people’s mistakes. Anyone looking to step into the world of American media can start by reading. live from america. Not because it’s a guide—author Javier Marín (Maracaibo, Venezuela, 58) hates guides—but because it’s a map told in the light, a map created by stumbling, intuition, and the mix of fear and ambition that come with every immigrant trying to tell a story in a place that hasn’t always wanted to hear it. The book reads like an intimate record of the rise of Latino television in the United States.

“I focused on telling real events,” the Venezuelan writer explains, shrugging his shoulders with the naturalness of someone who admits to minor faults. But each chapter reveals something more than research: the rawness of a job that demands precision in a country where speed is prized, the need to make a name for yourself without losing your identity, and the constant struggle to translate from Spanish to English to survive in the continent’s most competitive newsrooms.

Mr. Marin was the owner of a media company specializing in business until he found his calling during the Venezuelan crisis. He came to the United States in 2000 with the idea of getting a master’s degree in business and working for a major newspaper for a few years before returning home. Temporary transition plan. However, the country he was returning to, Venezuela, changed during his studies there. “In fact, authoritarianism has become stronger,” he says, without any drama, in the same tone as the economists he interviewed when he was an economic reporter. Like many people in the first wave of migration, he decided to stay.

his first impulse was to try crossover For English media. “If you’re not a native speaker, it’s very difficult. I think it’s one of the most difficult professions to get past,” he admits. So he changed strategy, leaning toward Spanish-language media even though he didn’t fully understand the demographic, economic, and cultural size of the Hispanic community. “I knew about its prosperity and the economic engine it represented, but I wasn’t an expert on its socio-economic composition. I wanted to specialize.”

In 2001 he knocked on the doors of Bloomberg, CNN and other Anglo-Saxon newsrooms, but September 11 changed everything. “The job market was a disaster,” he recalls. Faced with that wall, he decided to research the Hispanic media business with the idea of starting his own media business. An idea was born that he describes in detail in his book. “We realized that the biggest business was Univision, and we started investigating that from scratch.”

He soon realized that something deeper was missing. That’s training. “There is no education to create a media business,” he says in the book’s epilogue. entrepreneurship “There is no number of media,” he argues, and even if there were, the world would want more than understanding revenue, profits, and costs. From there he was hooked. His research began as a personal study rather than an editorial project. “I discovered something incredible, but at first I was just trying to figure it out.”

That obsession eventually led him to the classroom. During a financial crisis, he decided to supplement his income by teaching a class on Latin American media at Tufts University. there he taught history clarion In Argentina, mercury In Chile, or globe In Brazil, the Venezuelan network and, of course, Univision, which accounted for almost a third of the courses. “The class was a success,” he recalls. “The majority were American students of all ages who were interested in history.” But repeating the same course material semester after semester left him exhausted. When he finished that stage, he was left with one conviction: “This story had great charm.”

He first considered publishing the book in 2008. He looked for collaborators and writers to help him organize his research. Nothing worked. “I had to write that book,” he admits. The final push came in 2019, just before the pandemic. Arizona State University (the only frontier studies school in the United States) offered me a one-year residency to write this book. And he said no again, because at that time he had business, responsibilities, and emergencies. But then the pandemic arrived, and for the first time in 20 years, he had time to sit down and write.

live from america This book not only tells the story of how a Spanish-language media empire was built in the United States, but also provides an intimate portrait of the Latin American magnates and strategists who saw the North as a necessary destination for their ambitions. Marin chronicles how the power struggle between Anglos and Hispanics inspires an epic melodrama whose audience is the United States’ Latino community.

Marin goes back in time to explain how the use of Spanish became integrated into the American cultural fabric. “I tried not to conform to racial or socio-economic descriptions of our community,” he says. This book shows how, in 1969, the Richard Nixon administration decided to group Spanish-speaking people within the United States under the label “Hispanic.” “It was a political invention,” he claims. This classification coincided with the rise of Univision’s immediate predecessor, the Spanish International Network (SIN), registered with the Ibero-American Telecommunications Institute (OTI) by Emilio Azcárraga Milmo. President Ronald Reagan proclaimed “National Hispanic Heritage Week” at one of the events held in Washington, which later became Hispanic Heritage Month.

This story is not an identity anecdote, but a starting point for thinking more broadly about power, representation, and what it means to be “Hispanic” in the United States. Therefore, when asked if they have ever experienced discrimination, they candidly answer, “Yes, I think all of us who have immigrated have felt the fear of being discriminated against, and I think we have all lived with discrimination in one way or another.”

Language, music, and the “Bad Bunny effect”

The advocacy of Spanish in the United States did not begin with musicians like Bad Bunny, but they accelerated an irreversible process. “There are already more than 60 million Spanish speakers in the United States,” Marin said. Music, he added, “is the most effective way to culturally influence the masses.” And his reckless invitation to Americans to learn Spanish before the Super Bowl, which he calls the “Bad Bunny effect,” solidified a truth uncomfortable for certain political circles.

Marin remembers that organized resistance against the Spaniards had been going on for decades. “Today we have a president who said we must speak English, not Spanish, and removed the Spanish page from the White House. … But the United States does not have an official language in its constitution. This country is already bilingual. Our culture is part of this country.”

The Venezuelan author asserts that this story should be delivered to leaders, businessmen, politicians, and dreamers who wish to delve into the origins of media empires, the psychological warfare of interracial shared leadership within organizations, and the evolution of audiences in social times. streamingArtificial Intelligence and Digital Platforms.