Of the hundreds of graves in Armero, in the Colombian municipality of Tolima department, most visitors simply walk past.

They walk a pilgrimage to the tombstone of Omaira Sánchez, the girl who became a symbol of the tragedy that ended the life of the city of Almelo and its 20,000 inhabitants 40 years ago.

Another 5,000 people were killed in a municipality adjacent to the city of Bogotá, located about 100 miles (160 kilometers) east of the city.

On November 13, 1985, the Nevado del Ruiz volcano in the Department of Tolima erupted. The flow melted 10% of the glacier cap and moved down the slope, taking in sediment, rock, and mud.

Torrents destroyed Armero, with victims crushed by rubble and suffocated by mud.

Omaira, 13, was trapped up to her neck. Her 60-hour ordeal was broadcast live with support from the local branch, rescue teams and journalists filming.

“Mom, if you listen to me, and I think I do, please pray that I will be able to walk again and that these people will help me,” the girl told the camera.

Without special machinery, rescue was impossible in the midst of the chaos.

Forty years later, Omaira’s tomb has become the most visited site in Almelo. Today it is a cemetery of ruins and graves battling tall grass.

pilgrimage center

A few meters from the grave, local merchants sell souvenirs. It is a strategic location as thousands of people pass through it every year.

Visitors pray, take photos, give thanks, and leave offerings. They revere Omaira as a saint.

“She was very brave. She believed in her rescue until the end. People say she performed miracles,” said Gloria Cartagena, a resident who frequently visits the monument.

Ricardo Solorzano also comes every month. Before his death five years ago, his wife, a native of Almelo, asked for his ashes to be scattered in Almelo.

“I came here because this girl gave me the courage and security to continue living. Any tribute[to Omaira]is more than deserved. She is an angel,” Solorzano says.

“Thank you, Omailita, for granting me the miracle I asked of you,” reads a stone tablet near the grave.

Another article read: “Thank you Omaira for the blessings you have received.”

A few years ago, they decided to surround the tombstones because so many messages had accumulated around them.

There are three other monuments for offerings and prayers around the place that is also believed to have been the place of his death.

Although the place is unrecognizable now, several years ago this street was where Omaira’s family, Sanchez and Garzón, and their neighbor Galeano lived.

“We believed this was the end of the world.”

On the day of the tragedy, Omaira’s mother, Aleida Garzón, a nurse, was in Bogotá solving some problems.

The girl remained at home with other family members. They were likely already asleep, as were many others in town, including Garzón’s neighbor and colleague Marta Galeano.

Galeano said she was confused and scared by the firefly lights that night.

After a few minutes, he realized that the light was not an insect, but the flashlights of his neighbors fleeing the avalanche.

She remembers waking up her husband, walking with her two children to a high point in the city, and passing over the dead on the way.

I didn’t know anything more about Omaira until I saw her in agony on TV hours later.

“We couldn’t believe it. We will never forget that horror. Such a well-behaved Catholic girl was able to energize the community with her dance,” Galeano said in a conversation with BBC Newsmundo, the BBC’s Spanish-language news service.

“Many years have passed, but we still remember it,” he added.

Almelo had approximately 29,000 residents before the disaster. It was a wealthy city with a thriving cotton industry.

Many survivors now live in neighboring municipalities such as Honda, Lleida and Almelo Guayabal, and Galeano welcomes me.

Months before the tragedy, several Colombian experts warned of the volcano’s threatening activity and the danger it posed to municipalities such as Armero, but there was no effective response from the authorities.

In addition to approximately 25,000 deaths, the disaster destroyed more than 5,300 homes and affected approximately 230,000 people.

In the absence of scientific or political explanations, faith provides an answer to the pain of people like Galeano, Garzón, and thousands of pilgrims.

“We thought this was the end of the world, but Omaira, the little girl, was destined to become an angel and a story of courage,” says Galeano.

“May God allow me to canonize her one day. She is my angel, my protector, my warrior,” said Omaira’s mother, Aleida Garzón, who now lives in Lleida, 15 kilometers south of the tragedy.

distraction

Not all Almelo survivors agree on how Omayra’s memory should be used by traders, the press, and visitors.

Garson, who frequently visits her daughter’s grave to ensure her safety, doesn’t seem entirely satisfied with the fact that tour guides read out her daughter’s words while she was alive, or otherwise pretend to be acquaintances of the family.

“Some people memorize stories on TikTok and charge for tours,” he says.

Maria Moreno, who runs the souvenir stall, earns most of her income during peak tourist seasons, such as this time of year in November, the first anniversary of the tragedy.

She agrees that her business is in the best possible shape, as the Girl’s Tomb is the busiest place in Armero and where visitors spend the most time.

He said he felt “sad” that his livelihood depended on such a tragic story, but said he had no other choice. “I wanted to get out of this situation and now it’s not possible.”

Some lament that the focus on Omayra’s monument takes focus away from the overall situation in Armero.

The family of one regular customer, Gloria Cartagena, points to plastic bottles and other waste thrown on the floor by others.

“They have installed more signs to commemorate the victims and show what happened on some roads, but it is sad to see the condition of many of the graves and buildings left behind: destroyed and full of graffiti,” says Cartagena.

Many bodies were never recovered. Some of the graves are empty, marking where the victims were last seen or where they are believed to have lived.

Some people correct their inscriptions by drawing a few days before their birthday. Others appear to have been abandoned for years.

The few houses that still stand, either crossed by tree roots or half-buried, were painted with the names of the families who lived there.

In the old cemetery, almost all the graves seem to have been destroyed. There are isolated bones within some niches.

Other children of Almelo

Many survivors of the tragedy feel that the state’s abandonment of Armero is not just physical.

And the media coverage of Omayra Sánchez’s case occupies too much space in the press and among visitors, with insufficient attention paid to the drama of other “Almelo children.”

This is the position of Francisco González, president of the Armando Armero Foundation, which is dedicated to reuniting families separated during tragedies and rebuilding the memory of municipalities.

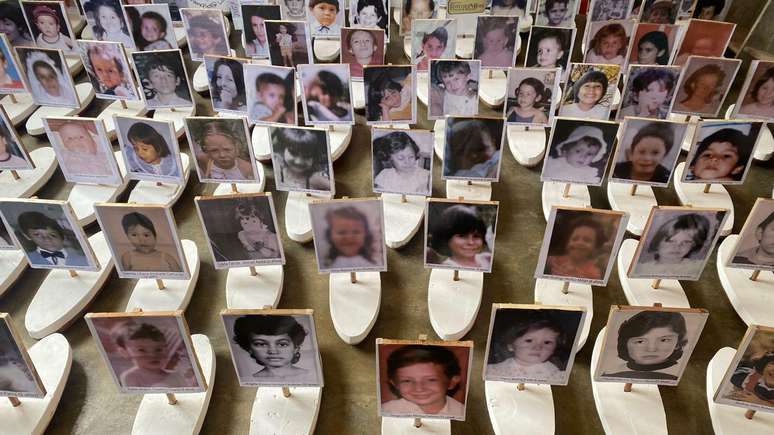

Armando Armero accused that around 500 children were being put up for adoption through “regular and irregular processes”.

Many of them are now adults and live in Colombia. Others ended up going abroad.

Gonzalez believes some people don’t even know their roots.

The Colombian Institute for Family Welfare (ICBF) argues that the irregularities reported by those affected must be investigated on a case-by-case basis due to flaws in the law at the time.

ICBF director Astrid Cáceres told BBC News Mundo that she would step up efforts to restore the memories of the victims and solve the adoption case.

Through Armando Armero, 400 families and 75 registered adopted children underwent DNA testing.

So far, genetic comparisons have led to four reunions.

Hundreds of victims still wait every anniversary for their families to reappear for commemorative events.

Omaira’s pilgrims, and hundreds of other children in Almelo, have one thing in common: a commitment to miracles.