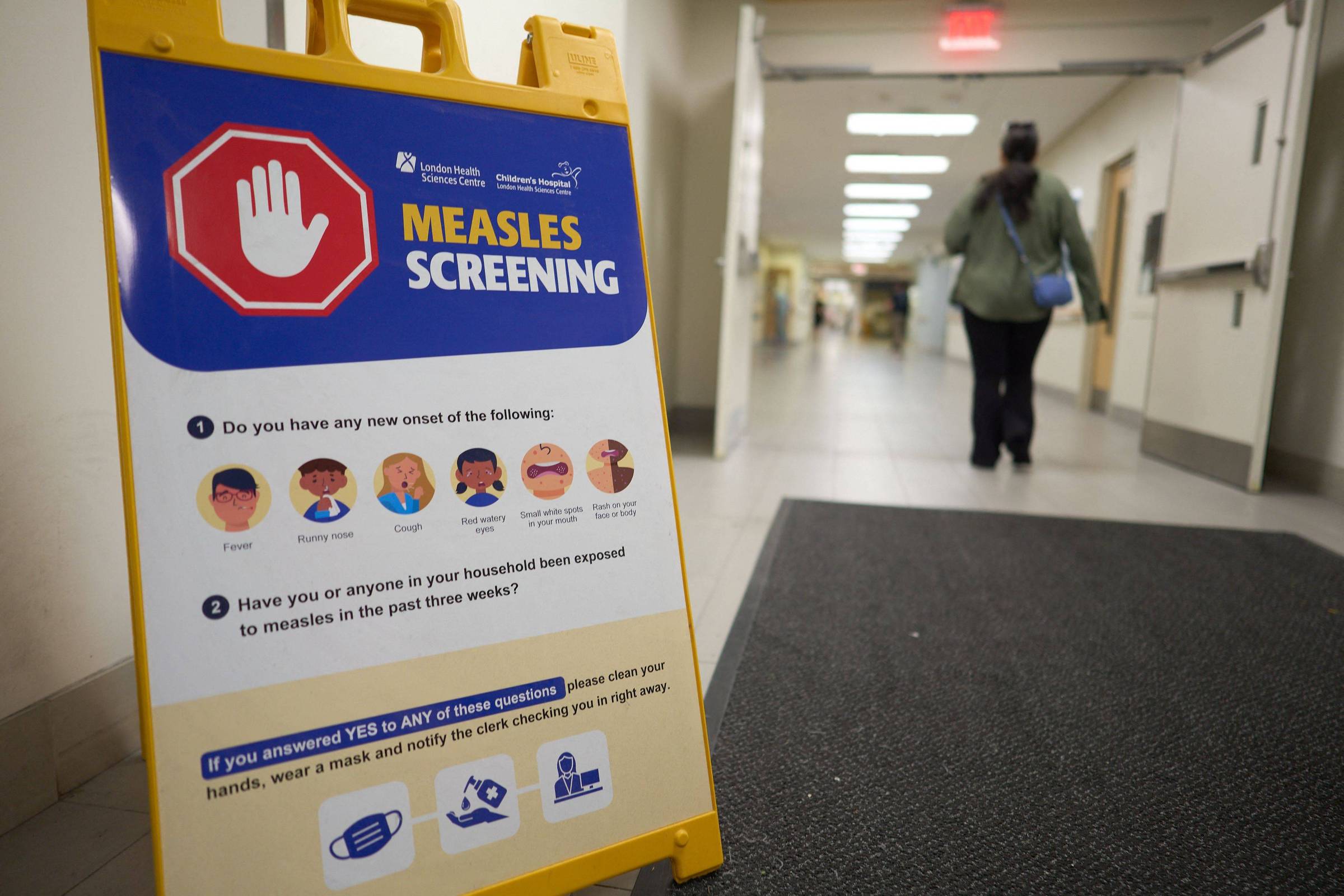

Canada has officially lost its status as a country that has eliminated measles, a highly contagious virus that had been considered eradicated in the country since 1998, the federal health agency announced Monday.

After several limited outbreaks in recent decades, the disease returned in October 2024. It has become established in several states and has been prevalent for more than 12 consecutive months, the World Health Organization (WHO) threshold for a country to lose eradication status.

The United States and Mexico also experienced outbreaks that sickened thousands of people over several months. If measles cases continue to be prevalent in these countries a year after the initial outbreak, the eradication status will be at risk.

The United States, with more than 1,600 reported cases, will reach that milestone in January, and Mexico, with more than 4,000 cases, will reach that milestone in February.

Other countries with active outbreaks are Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, and Paraguay.

Alvaro Whittenberry, an immunization expert at the Pan American Health Organization, said it could take years for countries to regain exclusion status. He cited the example of Brazil, which lost its status in 2019, stopped the spread of endemic diseases in 2022, and regained its status in 2024.

How did Canada get here?

Declining vaccination rates and a clash between post-pandemic politics and public health policy contributed to the spread of infections in Canada.

Across Canada, 79 per cent of seven-year-olds were fully vaccinated against measles in 2021, the most recent year for which data is available, down from 83 per cent in 2019. This is far below the 95% threshold that experts say is needed to stop the spread of the virus.

In Canada, the highest concentration of infections is in the western province of Alberta, which emphasizes the freedom of individuals to refuse vaccination. Politicians and health officials clashed in April when the province’s top doctor resigned during a new wave of virus infections in Canada.

Culturally conservative Mennonite communities are at the center of the outbreak, said Marina Salvadori, a pediatric infectious disease researcher and medical advisor with the Public Health Agency of Canada. Historically, these groups have been less likely to accept vaccines, although governments have not provided accurate demographic data on cases.

The virus has also appeared in several other places with significant Mennonite communities, including West Texas in the United States and Chihuahua, Mexico.

Canadian public health experts are concerned that measles is a harbinger of a resurgence of other diseases previously thought to be under control, such as polio.

“Measles is the canary in the coal mine because of its incredible transmissibility,” said Brian Ward, a professor of infectious diseases at McGill University in Montreal.

When a country loses disease-free status, the entire Americas is considered to have lost that status as well. This designation is made by an independent expert group at PAHO (Pan American Health Organization), the WHO regional office representing 35 countries in the Americas.

What is Canada doing now?

A spokesperson for Canada’s Health Minister Marjorie Michel said they are “closely monitoring the situation” and working with provincial health officials. Madison McKee, a spokeswoman for the state’s health secretary, said the number of new cases has fallen to single digits in recent months.

“Public health officials have implemented a targeted vaccination campaign, expanded clinic hours, and launched a statewide outreach effort,” McKee wrote in an email. “More than 130,000 measles vaccines have been administered across Alberta since March, a 50 per cent increase compared to the same period last year.”

To regain exclusion status, Canada would need to prove there was no endemic spread of the virus for 12 consecutive months.

To do that, public health experts say Canada needs to expand vaccination coverage.

“This is really the best tool in our arsenal to end the outbreak,” said Shelley Bolotin, director of the Center for Vaccine Preventable Diseases at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health.