During his first and second years at ESO, Juan attended afternoon review classes at the Ramon y Cajal public high school in Albacete. “It helped me in all areas, but especially mathematics, equations, language and syntax, which were very difficult for me,” he comments. That helped him avoid problems during the slippery transition between primary and secondary education, said his father, Juan González, a public school teacher. My only regret is that this program was only available for the first two years, and my son was unable to attend this year, his third year. “Now he goes to the academy on Tuesdays and Thursdays at the same time. It’s the same, but before it was free, now he pays. And not only is it worse because of financial problems, but he was more motivated before. The lessons were in the education center, so he was with his classmates and he was reviewing exactly what the teacher said in the morning,” he says.

Among developed countries, Spain has very few secondary education institutions that offer review lessons to students in their own secondary schools. 40% do so, 25 points below the OECD average and a far cry from South Korea and the UK, two of the countries with the best results in the biggest international assessment, the PISA report, with rates above 90%.

Experts say the absence of such programs will slow down improvements in educational outcomes, especially for children who do not live in wealthy families, while increasing the private extracurricular sector, so-called shadow education, to which families have been allocated €1.7 billion in 2021. According to EsadeEcPol’s head of education, Lucas Gortázar, Spain’s lag in this area is related to the country’s poor tradition of personalizing education. “Most of the spending increases are aimed at increasing the number of teachers and reducing the number of students per class. This means less ability to provide individualized attention to students, instead of a slightly better general response for all students.”

Gorthasar believes the root cause is pure political economy. “The people who benefit from these programs tend to be students with gaps in the curriculum or students who are socio-economically disadvantaged. We know that these types of families have lower-than-average turnout. But in front of them is a larger group of teachers and many middle-class families who are voting more and always want a general reduction in the number of students per class.”

Juan González, the father of a high school student in Albacete, currently pays 60 euros a month for private classes. For Sonia, 35, the mother of a student at Virgen del Remedio public school in Alicante, this amount would be extremely difficult. She attended free enrichment classes at the center during ESO’s first two years. “My husband and I are both unemployed and have three children, so we couldn’t take him to private lessons for financial reasons, which helped him get ahead in the career,” she says.

The holes in the Spanish education system in this area are becoming even more serious, added the head of education at EsadeEcPol. With an increasing number of international students, some of whom need support to catch up with their studies, the early dropout rate is three times higher than in native speakers.

From not understanding classes to science baccalaureate

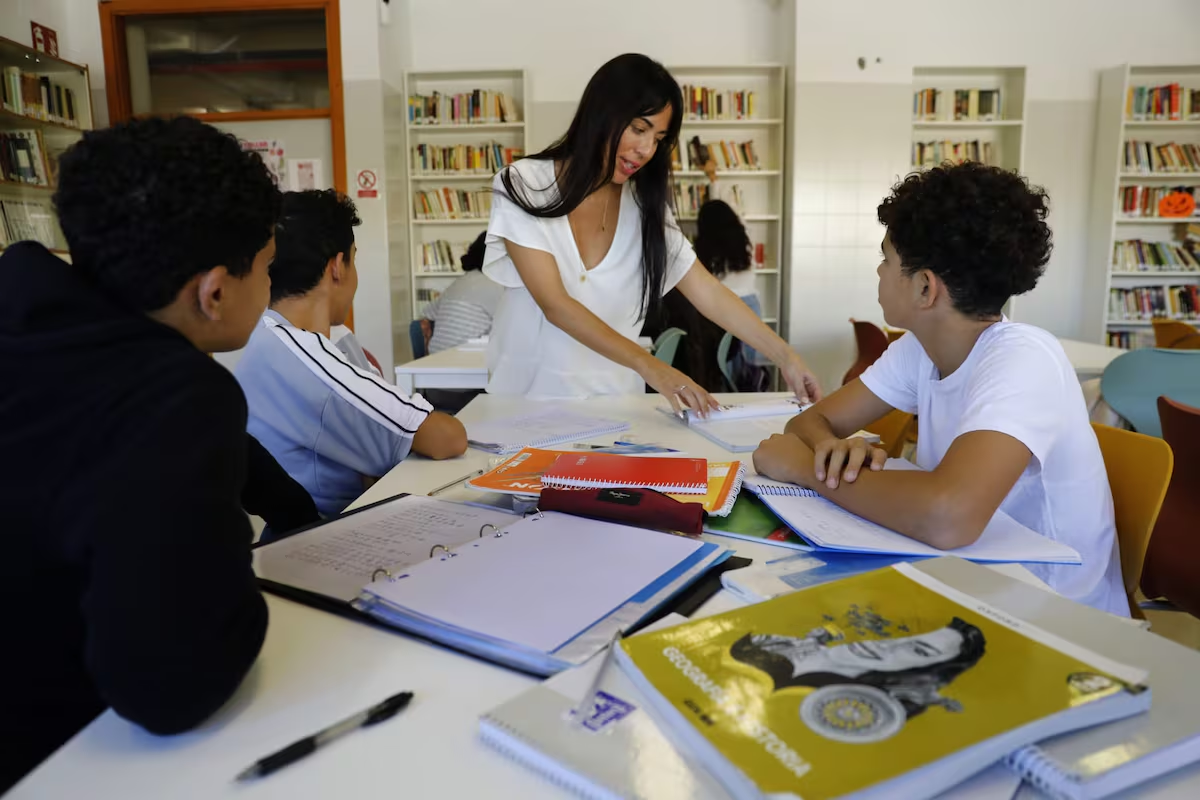

The case of Fatima, a 15-year-old ESO fourth-year student at the Public Institute of Guadarrama in Madrid, is an example of the usefulness of these programs. This teenager arrived in Spain during his first year at ESO, but as soon as he joined the class, he was convinced he would repeat the grade because he couldn’t speak Spanish. His center offered two-hour review classes in small groups two days a week. He signed up and managed to save the year. “They helped me a lot, especially in languages, history and biology. In mathematics, I didn’t need the numbers as much because I could understand them,” he says. Fatima’s mother is a housewife and her father works in a restaurant. She is studying her fourth year of ESO and is doing well. I plan on getting a Science Baccalaureate and then perhaps studying medicine.

Rosa Rocha, director of the institute Fatima is working on, says that in a situation like Spain, where almost all public secondary schools (and increasingly primary schools) have classes in the morning, public review classes have social as well as academic utility. “Not only does it help them improve academically, but many of the kids who come here end up spending the afternoon alone.”

On a positive note, the heads of educational institutions consulted to produce this report agreed that the additional classes they offer do not cover real needs. For example, Rocha regrets that the Madrid-funded program began in January and that many students have “already failed the first assessment.” Jesús Medrano, director of research at the Cinco Villas Public Institute in Ejaa de los Caballeros, Zaragoza, added: “This program is important, but it is also inadequate. With our staff, we can serve about 30 students in two afternoons a week, but then we need to give them more time and serve more students.” These 30 children represent about 5% of the center’s students. This rate is similar to that achieved by support classes at other centres, which are usually limited to the most challenged students, and usually only to the first and second years of ESO.

Directors’ efforts

There are other autonomous communities that fund these types of classes, such as Castilla y León and Euskadi. And the Department of Education itself is doing that through its PROA+ program. Nevertheless, in many educational institutions, free extracurricular activities are offered thanks to the efforts of administrators, the cooperation of teachers (sometimes teachers and volunteers outside the center), and, in public education, overcoming the rigid schedule scaffolding of the center.

At the Ramón y Cajal Institute in Albacete, for example, director Carlos Gardón was able to launch the project thanks to the part-time contract of one of the administrators and the use of student volunteers from the Faculty of Education as reviewers. And at Virgen del Remedio in Alicante, its director Mar Sierra achieved this by taking advantage of the fact that the institute has vocational cycle teachers in the afternoons. This year, since VET recruitment in her neighborhood was concentrated at another institution and she had no VET recruitment, Sierra managed to get by by hiring a teacher with funding from the Ministry of Education. However, we had to reduce the number of students participating from 40 to 20 and the scope by ESO’s first year.