credit, Benoît Clarisse/Alban Michel

-

- author, Juan Francisco Alonso

- roll, BBC News World

The homo sapiens We are currently the only human species walking the earth, but that hasn’t always been the case. About 50,000 years ago, our family shared the Earth with at least two other groups: Neanderthals and Denisovans.

There is extensive archaeological and paleontological evidence for Neanderthals, who lived in the western half of Eurasia.

The first discovery was made in 1856, when workers discovered a set of bones, initially identified as the remains of a bear, in a quarry in the Neander Valley (Germany).

However, almost nothing was known about the Denisovans until this century.

The lack of information intrigues researchers, especially since recent studies suggest that this lineage plays a fundamental role in the continuation of humanity.

“Missing link?”

Denisovans came to the attention of science in 2010, almost by accident.

That year, researchers at Germany’s Max Planck Institute extracted DNA from fossilized fingers and molars discovered two years earlier in a cave in Denisova, Siberia, Russia. These fragments were thought to belong to Neanderthals.

However, the results of the genetic analysis were surprising.

“Scientists were hoping to find a Neanderthal genome, but when we looked at it, we realized it was something unique,” Fernando Villanea, a professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado Boulder, said in an interview with BBC News Mundo, the BBC’s Spanish-language news service.

“The number of differences observed in the genomes is comparable to that between Neanderthals and humans, indicating the existence of a new species,” said a geneticist who specializes in prehistoric human populations.

This new strain is named after the location where it was discovered.

credit, Getty Images

But who are the Denisovans and how did they come to be?

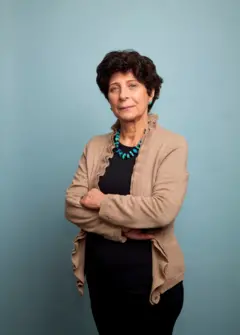

“It was a group that split off from our Sapiens lineage about a million years ago,” says Silvana Condemi, a French paleoanthropologist and one of the biggest experts on the subject.

According to Condemi, “The most likely hypothesis is that the divergence between lineages (Neanderthals and Denisovans) occurred during the exodus from Africa, which we know occurred during the exodus from Africa.” homo heidelbergensis“This is a species that arrived in Europe with the ability to use fire during a very long and severe interglacial period,” said author Condemi. The secret world of Denisova (The secret world of the Denisovans, paraphrased).

“Without a doubt, climatic conditions explain the separation of Neanderthals and Denisovans, as glaciers separated their territories,” added Condemi, who is also director of research at the French National Center for Scientific Research, one of the country’s main scientific institutions.

But why has this group remained under the radar for so long? Experts blame this on a lack of fossil remains and errors in the classification of known finds.

credit, Alban Michel

genetic inheritance

The Denisovans occupied large areas of East Asia and even reached Oceania.

In July 2024, Chinese researchers detected Denisovan DNA fragments in a skull recovered in northern China. Similar findings are seen in two jaws from Tibet and Taiwan.

“These data suggest that Denisovans lived not only in coastal and tropical regions, but also in cold, mountainous environments,” said Villanea, of the University of Colorado Boulder.

As Denisovans expanded geographically, they coexisted and mixed with other human species they encountered.

“The first time homo sapiens They left Africa, came into contact with Neanderthals, and hybridized. Then the same thing happened to the Denisovans who moved east,” Kondemi said.

Recent studies have shown that this “heterogeneous generation” contributed to ensuring the survival of organisms. sapiens.

“Years of research have identified several unique genes that Denisovans carried that gave them an advantage in certain climates and regions (…) and some of these Denisovan genetic variants are still present in modern humans,” Villanea, from the University of Colorado Boulder, explained.

credit, Getty Images

For example, Kondemi points to the EPAS-1 gene, which is present in more than 80% of Tibet’s current population. “This Denisovan gene improves oxygen transport, which is essential for people living at high altitudes.”

The TBX15 and WARS2 genes are present in very specific variants on chromosome 1, whose origins can be traced back to the Denisovans and were discovered in some populations living in the highlands of Asia, said Condemi of France’s National Center for Scientific Research.

“These genes play a role in body development, particularly in the distribution of brown adipose tissue, which is used to generate heat in cold regions,” Condemi explains.

credit, Samuel Kirzenbaum

to America

Another Denisovan gene found in Neanderthal fossils and modern humans is MUC19, which is involved in the production of a protein that forms the mucosal barrier in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts that protects tissues from saliva and pathogens.

“This gene is found in one in three people with American Indian ancestry,” says Villanea, who participated in the study with scientists from Mexico, Denmark, Italy, France and Ireland.

But did Denisovans reach America? “No, but it’s because of your genes,” Condemi replied. “Asians, like Americans and Latin Americans, have Neanderthal and Denisovan genes, because some of America’s indigenous peoples come from Asia.”

“If you are from South America and you send your DNA to an American company that does research for US$100 (about R530), they will find that you have Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA. And depending on your origin, you may have twice as much Denisovan DNA as the one that came through the Bering Strait and the one that arrived later with people from the Pacific Ocean,” says Condemi.

However, among Latin Americans with European ancestry, Neanderthal genetic backgrounds predominate, Condemi explains.

But returning to the MUC19 gene, Villanea notes that the gene is suspected to have conferred an “advantage” on the immunological defenses of some parts of the American population, which may have contributed to their adaptation to continental conditions.

credit, Norwegian Nobel Prize Committee

something like a history book

For Condemi, the discovery of the Denisovans was a turning point in understanding human origins and how to investigate the past.

“Although paleoanthropology was once based on bones, it now collaborates with many other fields such as genetics, biology and botany,” the researchers say.

The use of genetics was revolutionary for these studies. “Our entire history can be read in our DNA,” Condemi says.

“It’s not just our personal history, our family history, our national history, but also our history as a species, our migrations, our encounters with disease, how we adapt to certain foods and environments. It’s all in our genes.”

Villanea follows the same path. “Although we don’t have complete skeletons, tools, or other references, the complete Denisovan genome has provided us with a lot of information.”

credit, Getty Images

There are more doubts than convictions

However, much remains to be learned about these ancestors and their disappearance.

According to Condemi, Denisovans had large heads, similar to Neanderthals in appearance.

“While Neanderthals had elongated dog-like faces with completely sideways cheeks, Denisovans had more pronounced cheekbones and very large teeth, much larger than Neanderthals or modern humans.”

Regarding the extinction of the Denisovans, Villanea says there is evidence to suggest a combination of factors.

“Although the fossil evidence we have is very incomplete, the genomes of individuals from the Altai Mountains (in Central Asia) provide certain clues. The genetic evidence indicates that the Denisovan community had very few individuals at least a few thousand years before extinction.”

Furthermore, “geological information shows that the end of the Denisovans coincided with the end of the European ice age, making it clear that they were adapted to living in cold ecosystems and probably relied on hunting extinct megafauna species.”

But at the same moment, homo sapiens I followed in their footsteps.

“The same climate change processes that destroyed the Denisovans pushed modern humans from the warmer regions of Africa to the Mediterranean Sea and the coasts of Asia, where they encountered the last Neanderthals and Denisovans, resulting in the legacy of humans today,” Villanea concludes.