Jose Gabriel Condorcanqui Noguera Born on March 19, 1738 in Slimana province. Cuscowithin the Curacus family of the last descendants. Inca of Vilcabamba. By paternal inheritance he assumed the chiefdoms of Sulimana, Pampamarca and Tungasca, which gave him a leading position in the indigenous world and before the colonial authorities. He received a thorough education at the Jesuit-run School of San Francisco de Borja in the imperial capital, where he learned Spanish, Quechua, and Latin, and was exposed to the Enlightenment ideas that were sweeping Europe and beginning to penetrate America.

This combination of pedigree, mentorship, and local leadership was unusual at the time. From a young age, Kondorkanki emerged as an intermediary between the community and the colonial power, repeatedly demanding relief from taxes and mining charges, and denouncing abuses by officials and magistrates. However, their appeals to the magistrates and the viceroy’s own requests were systematically ignored.

mid-18th century, bourbon reform And the opening of new commercial circuits (such as the opening of the port of Buenos Aires) increased financial and economic pressure on indigenous peoples and merchants in the southern Andean region. Conditions such as overexploitation, extortion of tribute, forced labor in the mines (mita), and abuse of chieftain’s honor turned the lives of thousands of indigenous people into a daily ordeal. Added to structural oppression were the commodity distribution system, alkabala (taxes), and the arbitrariness of the workshop.

In the face of colonial authorities’ indifference, Kondorkanki realized that legal routes were reaching their limits. The quest for justice was no longer made possible through petitions and deeds, but through rebellion.

On November 4, 1780, Condorcanqui’s life and the history of Peru changed forever. After the arrest and execution of Tinta Mayor Antonio de Arriaga on charges of repeated abuse and extortion; Tupac Amaru II The new name he adopted in honor of his ancestors started a call for rebellion. The movement quickly spread throughout the southern Andean region, upper Peru, and the viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata.

Unlike later independence struggles, Tupac Amaru II’s original aim was not a definitive break with Spanish monarchy, but rather an end to practices such as the system of mitas, obrajes, and collegimientos, the fraudulent collection of taxes and duties, and the forced distribution of goods. In an unprecedented move in Latin America, on November 16, 1780, he issued a proclamation abolishing black slavery. “I prohibit black slavery.”he ordered in anticipation of its abolition in other parts of the continent by a few decades.

the rebellion won its first major victory Battle of Sangalala (November 18, 1780), the rebels annihilated the Royalist army under Tiburcio Landa. Despite the momentum of his victory, Tupac Amaru II chose not to immediately march on Cuzco, which facilitated the reorganization of the Viceroy’s defenses and the arrival of reinforcements from Lima and Buenos Aires.

The movement launched a siege that lasted two months, but was unable to overcome internal resistance, due in part to fragmentation and the absence of a more coordinated military strategy. The Viceroy’s repression intensified with the arrival of 17,000 troops led by the visitor José Antonio Areche and Viceroy Agustín de Jauregui.

On April 6, 1781, Tupac Amaru II was taken prisoner after his defeat at Chechakpe and the betrayal of his entourage. He was chained, severely tortured, and taken to Cusco.

On May 18, 1781, José Gabriel Condorcánqui was publicly executed in Cusco’s Plaza de Armas, after witnessing the death of his wife Michaela Bastidas, their children, and his followers. The unusually brutal punishment was aimed at instilling fear: his body was mutilated and scattered in nearby towns as a lesson.

Far from being put out, the rebellion continued under other leaders in Upper Peru, such as Diego Cristóbal Tupac Amaru and Tupac Catari, who besieged La Paz for months. In parallel, colonial responses erased indigenous symbols and banned the Quechua language, indigenous clothing, and references to the Incan past. Despite the repression, the movement left an indelible mark on both the region and its subsequent struggles.

Tupac Amaru II’s rebellion became a beacon of inspiration for liberation processes and indigenous movements, from New Granada and the Comuneros of Chile to the struggles of the 19th century. San Martín’s independence movement would take up the promise of liberalism against slaves, and in the 20th century his figure would become a symbol of social struggle and indigenous dignity.

Throughout history, the image and message Tupac Amaru II They were reinterpreted by national projects and social movements. The government of Juan Velasco Alvarado (1968-1975) rescued him as a founding figure and imprinted his face on public squares, stamps, and monuments. It also influenced political movements such as Peru’s MRTA and Uruguay’s Tupamaros.

In pop culture, his name has crossed borders: American rapper tupac shakur The name was named in his honor, and many organizations in Latin America claim his heritage. On a symbolic level, it is associated with the Inkali myth, the hope of restoration and redemption of the Andes.

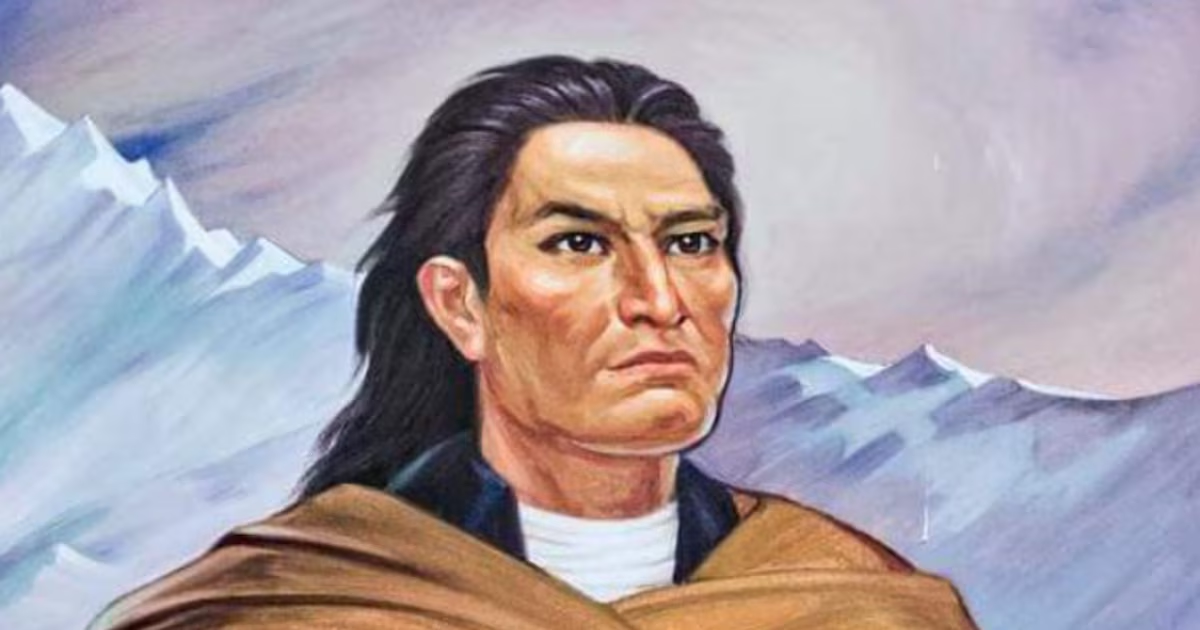

Although no authenticated contemporary portrait exists, contemporary accounts describe him as a man of noble demeanor, tall stature, an aquiline nose, and a strong voice. He was multilingual, fluent in Spanish and Quechua, and had a high degree of cross-cultural education, a rarity in the colonial era.

Today, Tupac Amaru II continues to lead marches, songs, artwork, and debates across the continent. He is a symbol of resistance to oppression, of the dignity of indigenous peoples and the incomplete promise of social justice in Latin America.

The name José Gabriel Condorcánchi lives on in history as synonymous with courage, rebellion, and hope. His life and sacrifice continue to remind us that the voices of those faced with injustice cannot be silenced.