image source, Getty Images

-

- author, Dario Brooks

- author title, BBC News Mundo@Hay Festival Arequipa 2025

About 500 years ago, to control pre-Hispanic peoples, Spanish explorers brought from Europe a weapon as fearsome as swords, crossbows, cannons, and horses: dogs.

Several expeditions of the Spanish royal family brought specimens of impressive breeds, such as the Spanish Arano and the German Bullenbeisser, and used them not only for missions and protection and surveillance of settlements, but also in attacks against indigenous peoples.

In the case of the march against the Incas, dogs were part of the strategy to terrorize the local population, who were surprised to see a pack with such aggressive instincts, even though they were aware of smaller, friendlier breeds of the animal.

“The dog becomes a weapon. Everything needed to be planned for its size, its training, and the way it beats the soldiers in charge,” author and Peruvian army colonel Carlos Enrique Freire explains to BBC Mundo.

His latest novel, “Tierra de canes”, follows one of the “apeladores” who train and protect Spanish troops during the Spanish occupation of Peru.

The work will be presented at the Hay Festival Arequipa 2025, which will be held in the Peruvian town from November 6th to 9th.

Leonsico and Vecerillo

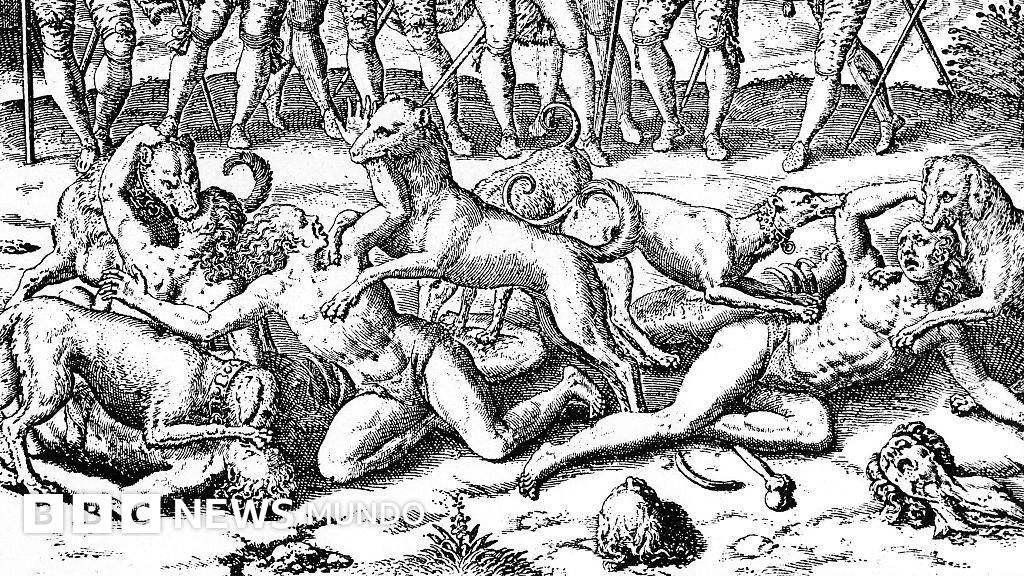

There is little literature about the presence of dogs in the Spanish ranks, only some representations in the art of the time.

Freire said he discovered the theme during a trip to Tumbes, the capital of the region of the same name in northwestern Peru, where he reviewed the works of contemporary chroniclers such as Spaniards Juan de Betanzos and Bartolomé de las Casas, who delved into indigenous culture and also described the abuses of conquest.

“They talk about these dogs and often use their characteristics to name them,” the authors explain. “The dogs arrived in Tumbes and wiped out the existing population.”

image source, Getty Images

In his fictional novel based on historical events, Tomás de Jerez becomes a dog handler for an impressive dog named Baldomero. However, since the first exploration of America, military leader Vasco Nunez de Balboa had dogs, including a Spanish dog named Leoncico.

It was part of the litter of Vecerillo, another fine dog that military leader Juan Ponce de Leon had kept since he marched into Hispaniola (now Puerto Rico).

“The relationship between Vasco Nuñez de Balboa and his dog Vecerillo was very deep,” Freire said.

“There’s a scene where he goes to see the Pacific Ocean for the first time, which actually happened. He reserves the right to see the ocean for the first time and to do so with his dog. All his officers and troops are left behind,” the writer explains of what he discovered during his research for the novel.

“It showed us the strong bond that exists between the two,” the dog and the dog’s trainer concluded.

Dogs were highly valued from the early days of Native American exploration and domination of territory in the early 16th century.

image source, Getty Images

weapons of war and punishment

When exploring the Amazon region, the Spanish brought up to 2,000 dogs with them. Francisco Pizarro was one of the men who led the raids that eventually overwhelmed the Inca Empire. One of the first places he passed was Tumbes.

“They didn’t have as many horses as is believed, and firearms were much more limited than what we know today,” Freire explains. “Where weapons, swords, and horses could not enter, dogs entered.”

The bulldogs attacked indigenous peoples who did not know of any breed of dog that was as large and trained for attack as the dogs brought from Europe.

“These dogs of the Spaniards were huge. Meat-eating animals were larger and these breeds were also pre-developed. So what they (indigenous peoples) saw were lions, not dogs,” he explains.

“Their role was to be military working dogs.”

image source, Getty Images

The use of packs was not limited to the conquests of the Inca Empire, but was a common practice in Mesoamerican territories, including many parts of the Caribbean, Central America, and the peoples of Mexico.

Dogs were used to intimidate and punish indigenous resistance.

“In the mid-sixteenth century, the Courtre de Amitatin was sentenced to death by stoning and burning at the stake for practicing incense and idolatry, for summoning evil spirits, for not observing or unwilling to observe the faith and Christian doctrine, for disregarding the cleanliness of the church, and for ordering the town’s Indians not to attend catechesis,” wrote the great Alonso López, mayor of Santa María. “De la Victoria and the Indian Round Toss”, a book edited by the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

In The Fate of Words, historian Miguel Leon Portilla rescues stories from the indigenous peoples of present-day Mexico.

“And their dogs are very, very big. Their ears are folded over and over, and their big jaws are quivering. They have swollen eyes, eyes like embers, yellow eyes, eyes of yellow flame. Thin bellies, ribbed bellies, lean bellies, very large and restless. They trot with their tongues out, panting. They have spots like a jaguar, and they have spots of different colors,” one story reads. Nahuatl language.

Freire tried to focus “Tierra des Canes” on Peru to “prevent the overflow of stories,” he explains. He believed that the crude ancient stories needed to be tempered.

“The use of violence in the text is descriptive, but not so much that people close the book and say, ‘Oh, that’s ugly.’ We needed a little balance,” the author says.

image source, Getty Images

abandonment

After controlling territory and population, dogs lost their main usefulness and over time became a headache for the Spaniards.

Further reducing the indigenous population was not an option, as they needed labor, including slave labor, and the presence and aggression of dogs began to become an inconvenience.

Freire explained that letters were sent by the King of Spain to various American commanders requesting that the dogs be exterminated to avoid further problems, even for the Spaniards themselves.

“They saw that if dogs were left alone, they would form packs and end up fighting both Spaniards and indigenous peoples. That’s why the Queen’s Ordinance on Dog Harm came into existence,” the authors say.

However, over the years of fighting together, the appeladores form a special bond with the dogs and vice versa, which also reflects the plot of “Tierra des Canes”.

“There’s a very strong bond between the dog and the soldier who carried it,” Freire said.

As a result, for some pastoralists, it was unthinkable to get rid of their favorite animals, despite royal orders.

As Spain tightened its grip on indigenous lands, dogs began to lose their character as weapons of war, and the memory of dogs as one of the keys to the conquest of indigenous peoples began to fade.

Little by little, its functions became more focused on protection and accompaniment. The only ones I remember are guys like Vecerillo and Leonsico.

image source, alpha guara

Subscribe here Sign up for our new newsletter and we’ll bring you the week’s best content every Friday.

Don’t forget that you can also receive notifications in the app. Please download and activate the latest version.